Atlantic Waste - Avian Mitigation Techniques

INTRODUCTION

Landfills attract many different species of scavenging wildlife but the most problematic are of the feathered variety. Not only are birds a nuisance to ongoing work at landfills but they also pose health and safety concerns to the surrounding area (Slate, et. al, 2000). Gulls have been found to carry an expansive range of pathogens from Salmonella, Campylobacter, the avian flu virus H5N1, E. coli, and the infectious bursal disease virus and given that these birds disperse across the surrounding landscape “the potential for large scale transmission of disease is great,” (Cook et. al, 2008). These large numbers of birds also produce large amounts of fecal matter. Bird fecal matter, while being unsightly and unsanitary, is also corrosive to equipment, the foremost mode of transmission for some of the pathogens listed above, and toxic to nearby water sources as the feces will raise bacterial counts. The large numbers of birds attracted to landfills are also a risk to nearby aviation. Because of this the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) recommends new landfills not be established “within five statute miles of an airport” (FAA, 2006).

Several studies have looked at different harassment methods to determine the most effective. Separated into two categories, active and passive management, these techniques should be tailored to the specific needs of the site. Passive management aims to make the habitat less attractive, so the target species are less likely to establish or return. However, modifications should be balanced as an alteration that is unappealing to one species may be attractive to another. Active mitigation directly harasses the wildlife away from the area using pyrotechnics, distress calls, falconry, and lethal removal amongst others.

PASSIVE

The most used passive technique was a combination of keeping the working face of the landfill small and capping the face thoroughly at the end of the workday and work week (Curtis et. al, 1993). Keeping the working face small reduced the area that the birds were comfortable landing and foraging on around the work. Loomacres has confirmed this at several at nearby landfills, the smaller the working face the fewer birds seen. It is also important to properly cap the working face “especially before weekends and holidays,” “if the landfill is not capped thoroughly for the weekend, birds are attracted to the exposed food, and numbers can increase dramatically by the following Monday” (Curtis et. al, 1993). In the study, Controlling Gulls at Landfills, bird species were ranked on how close they were willing to forage next to the heavy equipment. While some species of gulls and egrets were comfortable close to the machinery the majority, from vultures to small perching birds, were kept at a distance by the ongoing work and many of those species were not seen at the landfill until the workday was over (Burger and Gochfeld, 1983). Capping the working face at the end of the workday thoroughly and consistently helps prevent these species from finding the landfill afterhours and coming back to it in the future.

Another form of passive mitigation is odor control. Scavengers such as the Turkey vulture often use their olfactory sense to find food and will be attracted by smells of decay. In the study, Sight or Smell, Turkey vultures were tested for visual or olfactory dependence, and showed a heavier reliance on their olfactory sense when locating food (Potier, et al, 2018). It is also possible that if a misting system is used for odor control, the food extract methyl anthranilate, which is an irritant to birds (acts like a mace), may be mixed in, further reducing avian presence.

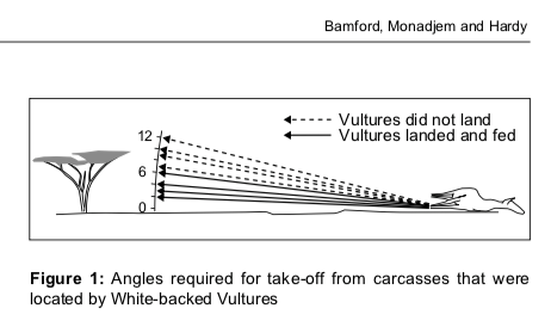

Another mitigation technique that focuses more on vultures and other large bodied birds is keeping the vegetation around the working face tall. Because vultures are large bodied and have a heavy wing load, which is increases the more they eat, their take-off incline must be less than 6 degrees from the ground to the top of the vegetation (See Fig. 1) (Bamford, 2009). If the degree of the height of the vegetation and distance to the food source is greater than the 6 the vultures will refuse to land and feed.

Landfills attract many different species of scavenging wildlife but the most problematic are of the feathered variety. Not only are birds a nuisance to ongoing work at landfills but they also pose health and safety concerns to the surrounding area (Slate, et. al, 2000). Gulls have been found to carry an expansive range of pathogens from Salmonella, Campylobacter, the avian flu virus H5N1, E. coli, and the infectious bursal disease virus and given that these birds disperse across the surrounding landscape “the potential for large scale transmission of disease is great,” (Cook et. al, 2008). These large numbers of birds also produce large amounts of fecal matter. Bird fecal matter, while being unsightly and unsanitary, is also corrosive to equipment, the foremost mode of transmission for some of the pathogens listed above, and toxic to nearby water sources as the feces will raise bacterial counts. The large numbers of birds attracted to landfills are also a risk to nearby aviation. Because of this the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) recommends new landfills not be established “within five statute miles of an airport” (FAA, 2006).

Several studies have looked at different harassment methods to determine the most effective. Separated into two categories, active and passive management, these techniques should be tailored to the specific needs of the site. Passive management aims to make the habitat less attractive, so the target species are less likely to establish or return. However, modifications should be balanced as an alteration that is unappealing to one species may be attractive to another. Active mitigation directly harasses the wildlife away from the area using pyrotechnics, distress calls, falconry, and lethal removal amongst others.

PASSIVE

The most used passive technique was a combination of keeping the working face of the landfill small and capping the face thoroughly at the end of the workday and work week (Curtis et. al, 1993). Keeping the working face small reduced the area that the birds were comfortable landing and foraging on around the work. Loomacres has confirmed this at several at nearby landfills, the smaller the working face the fewer birds seen. It is also important to properly cap the working face “especially before weekends and holidays,” “if the landfill is not capped thoroughly for the weekend, birds are attracted to the exposed food, and numbers can increase dramatically by the following Monday” (Curtis et. al, 1993). In the study, Controlling Gulls at Landfills, bird species were ranked on how close they were willing to forage next to the heavy equipment. While some species of gulls and egrets were comfortable close to the machinery the majority, from vultures to small perching birds, were kept at a distance by the ongoing work and many of those species were not seen at the landfill until the workday was over (Burger and Gochfeld, 1983). Capping the working face at the end of the workday thoroughly and consistently helps prevent these species from finding the landfill afterhours and coming back to it in the future.

Another form of passive mitigation is odor control. Scavengers such as the Turkey vulture often use their olfactory sense to find food and will be attracted by smells of decay. In the study, Sight or Smell, Turkey vultures were tested for visual or olfactory dependence, and showed a heavier reliance on their olfactory sense when locating food (Potier, et al, 2018). It is also possible that if a misting system is used for odor control, the food extract methyl anthranilate, which is an irritant to birds (acts like a mace), may be mixed in, further reducing avian presence.

Another mitigation technique that focuses more on vultures and other large bodied birds is keeping the vegetation around the working face tall. Because vultures are large bodied and have a heavy wing load, which is increases the more they eat, their take-off incline must be less than 6 degrees from the ground to the top of the vegetation (See Fig. 1) (Bamford, 2009). If the degree of the height of the vegetation and distance to the food source is greater than the 6 the vultures will refuse to land and feed.

ACTIVE

Of the active harassment techniques studied, distress calls or pyrotechnics paired with lethal control, falconry, and live ammunition were found to be the most effective; visual harassment used standalone was quickly became habituated and was ineffective long term (Cook et. al, 2008). Habituation occurs when the target species becomes used to the scare devices and act unaffected. Pairing distress calls or pyrotechnics with lethal control limited the effects of habituation. However, while lethal control is effective to reduce population numbers and the minimize the effects of habituation it should meet humane euthanasia standards set by AVMA. The servicing entity should also consider the public eye during removal to avoid negative attention.

In one study, the combination of using the product Posi-Seal (PS) in addition to pyrotechnics dropped gull numbers from 2,400 to 50-60 gulls per day.

The PS worked as both a passive physical deterrent by coating the working face and making it more difficult for the birds to forage and as an active harassment technique by scaring the gulls during the application process. "The act of spraying PS frightened the gulls, and a brief application of PS could deter birds from feeding for an hour or more,” “After 4 days of being deprived of food via the harassment- spraying of PS, gull numbers were down nearly 50%” (Curtis et. al, 1993).

OFFSITE ATTRACTANTS

When forming a management plan, it is important to consider nearby offsite attractants. Vultures for example are often attracted to communication and water towers for communal roosting sites (Ball, 2009). The height of these towers is advantageous to vultures allowing them to see greater panoramic distances, as well as providing easy landing and perching areas, and upward air currents to facilitate take off and altitude gain (Avery, 2002). During the winter solid structures like water towers provide additional roosting advantages by blocking wind as well as reflecting sunlight and warming the birds (Ball, 2009). Hanging taxidermic effigies, vulture carcasses, or painted decoys is usually enough to dissuade the vultures from maintaining the tower as their roost location (Avery, 2002). Multiple studies have shown that vultures do not readily habituate to effigies and will stay away as long as the effigy is still present (Avery, 2002 and Ball, 2009). Ball demonstrated that one effigy is as effective as two (2009) and Avery reported that the vultures stayed away from the towers anywhere from 2 – 7 months after the effigy was removed (2002). In order for the effigies to be effective they must be hung upside down (mimicking death) and placed to be widely seen by incoming birds (Ball, 2009). Visual mimicking is key, the more realistic looking the effigy the more effective it is, thus in ranking order of most effective – taxidermic effigies were long lasting as well realistic looking, however good quality taxidermy can be expensive (Ball paid $200 per effigy) and eventually the effigy will become weathered and disintegrate; untreated carcasses were realistic but will rot away and need to be replaced, as well as the rotting carcass will be visually and olfactorily displeasing to workers on the tower; painted decoys were less effective with some vultures staying around the towers but still with numbers significantly decreased, however decoys have the advantage of withstanding the weather and being cheap (Avery, 2002).

These studies were done with the intention of monitoring and disrupting roost sites, it is unknown if effigies will have the same effect at feeding sites. However, disrupting nearby roosts will sometimes change the communities forage center point. Avery documented that a pig farm saw significant decrease in vulture numbers (thus decreased predation on newborn piglets) when the nearby communication tower was hung with an effigy (2002).

CONCLUSION

For passive mitigation, it is highly recommended that the landfill keep the working face minimal and cap the face at the end of each workday and work week and if possible, allow the surrounding vegetation to grow tall. Of the active techniques, many were successful but, with exception of lethal control and falconry, all showed effects of habituation after a period of time. For maximum effectiveness and to avoid habituation multiple techniques should be used as well as rotated so the birds do not become used to one form of harassment. And if possible, nearby vulture roosts should be disrupted to lower the number of vultures in the area. It is also possible that hanging an effigy on or near the landfill itself might persuade vultures to feed elsewhere.

Works Cited

Avery, Michael et al. “Dispersing Vulture Roosts on Communication Towers”. Journal of Raptor Research, 2002, vol. 36, pp. 45-50

Ball, Steven A. “Suspending Vulture Effigies from Roosts to Reduce Bird Strikes.” Human-Wildlife Conflicts, vol. 3, no. 2, 2009, pp. 257–259. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24875714.

Bamford, Andrew J, et al. “An Effect of Vegetation Structure on Carcass Exploitation by Vultures in an African Savanna.” Ostrich, vol. 80, no. 3, 1 Aug. 2009, pp. 135–137., doi:10.2989/ostrich.2009.80.3.2.965.

Baxter, Andrew T., and Andrew P. Robinson. “A Comparison of Scavenging Bird Deterrence Techniques at UK Landfill Sites.” International Journal of Pest Management, vol. 53, no. 4, 2007, pp. 347–356., doi:10.1080/09670870701421444.

Burger, Joanna, and Michael Gochfeld. “Behavior of Nine Avian Species at a Florida Garbage Dump.” Colonial Waterbirds, vol. 6, 1983, pp. 54–63., doi:10.2307/1520967.

Cook, Aonghais & Rushton, Steven & Allan, John & Baxter, Andrew. “An Evaluation of Techniques to Control Problem Bird Species on Landfill Sites.” Environmental Management, 2008, 41. 834-43. 10.1007/s00267-008-9077-7.

Curtis, Paul D.; Smith, Charles R.; and Evans, William, "Techniques for Reducing Bird Use at Nanticoke Landfill Near E. A. Link Airport, Broome County, New York" (1993). 6 - Sixth Eastern Wildlife Damage Control Conference, 1993.

Federal Aviation Administration. Advisory Circular 150/5200 34A “Construction or Establishment of Landfills Near Public Airports.” 2006.

Potier, Simon, et al. “Sight or Smell: Which Senses Do Scavenging Raptors Use to Find Food?” Animal Cognition, vol. 22, no. 1, 26 Oct. 2018, pp. 49–59., doi:10.1007/s10071-018-1220-0.

Slate, Dennis, et al. “Controlling Gulls at Landfills.” Proceedings of the Vertebrate Pest Conference, vol. 19, 2000, doi:10.5070/v419110223.

Loomacres Wildlife Management

E. Darby Albrecht

Kai Schafer

Brooke Morgan

800-243-1462

[email protected]

Of the active harassment techniques studied, distress calls or pyrotechnics paired with lethal control, falconry, and live ammunition were found to be the most effective; visual harassment used standalone was quickly became habituated and was ineffective long term (Cook et. al, 2008). Habituation occurs when the target species becomes used to the scare devices and act unaffected. Pairing distress calls or pyrotechnics with lethal control limited the effects of habituation. However, while lethal control is effective to reduce population numbers and the minimize the effects of habituation it should meet humane euthanasia standards set by AVMA. The servicing entity should also consider the public eye during removal to avoid negative attention.

In one study, the combination of using the product Posi-Seal (PS) in addition to pyrotechnics dropped gull numbers from 2,400 to 50-60 gulls per day.

The PS worked as both a passive physical deterrent by coating the working face and making it more difficult for the birds to forage and as an active harassment technique by scaring the gulls during the application process. "The act of spraying PS frightened the gulls, and a brief application of PS could deter birds from feeding for an hour or more,” “After 4 days of being deprived of food via the harassment- spraying of PS, gull numbers were down nearly 50%” (Curtis et. al, 1993).

OFFSITE ATTRACTANTS

When forming a management plan, it is important to consider nearby offsite attractants. Vultures for example are often attracted to communication and water towers for communal roosting sites (Ball, 2009). The height of these towers is advantageous to vultures allowing them to see greater panoramic distances, as well as providing easy landing and perching areas, and upward air currents to facilitate take off and altitude gain (Avery, 2002). During the winter solid structures like water towers provide additional roosting advantages by blocking wind as well as reflecting sunlight and warming the birds (Ball, 2009). Hanging taxidermic effigies, vulture carcasses, or painted decoys is usually enough to dissuade the vultures from maintaining the tower as their roost location (Avery, 2002). Multiple studies have shown that vultures do not readily habituate to effigies and will stay away as long as the effigy is still present (Avery, 2002 and Ball, 2009). Ball demonstrated that one effigy is as effective as two (2009) and Avery reported that the vultures stayed away from the towers anywhere from 2 – 7 months after the effigy was removed (2002). In order for the effigies to be effective they must be hung upside down (mimicking death) and placed to be widely seen by incoming birds (Ball, 2009). Visual mimicking is key, the more realistic looking the effigy the more effective it is, thus in ranking order of most effective – taxidermic effigies were long lasting as well realistic looking, however good quality taxidermy can be expensive (Ball paid $200 per effigy) and eventually the effigy will become weathered and disintegrate; untreated carcasses were realistic but will rot away and need to be replaced, as well as the rotting carcass will be visually and olfactorily displeasing to workers on the tower; painted decoys were less effective with some vultures staying around the towers but still with numbers significantly decreased, however decoys have the advantage of withstanding the weather and being cheap (Avery, 2002).

These studies were done with the intention of monitoring and disrupting roost sites, it is unknown if effigies will have the same effect at feeding sites. However, disrupting nearby roosts will sometimes change the communities forage center point. Avery documented that a pig farm saw significant decrease in vulture numbers (thus decreased predation on newborn piglets) when the nearby communication tower was hung with an effigy (2002).

CONCLUSION

For passive mitigation, it is highly recommended that the landfill keep the working face minimal and cap the face at the end of each workday and work week and if possible, allow the surrounding vegetation to grow tall. Of the active techniques, many were successful but, with exception of lethal control and falconry, all showed effects of habituation after a period of time. For maximum effectiveness and to avoid habituation multiple techniques should be used as well as rotated so the birds do not become used to one form of harassment. And if possible, nearby vulture roosts should be disrupted to lower the number of vultures in the area. It is also possible that hanging an effigy on or near the landfill itself might persuade vultures to feed elsewhere.

Works Cited

Avery, Michael et al. “Dispersing Vulture Roosts on Communication Towers”. Journal of Raptor Research, 2002, vol. 36, pp. 45-50

Ball, Steven A. “Suspending Vulture Effigies from Roosts to Reduce Bird Strikes.” Human-Wildlife Conflicts, vol. 3, no. 2, 2009, pp. 257–259. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24875714.

Bamford, Andrew J, et al. “An Effect of Vegetation Structure on Carcass Exploitation by Vultures in an African Savanna.” Ostrich, vol. 80, no. 3, 1 Aug. 2009, pp. 135–137., doi:10.2989/ostrich.2009.80.3.2.965.

Baxter, Andrew T., and Andrew P. Robinson. “A Comparison of Scavenging Bird Deterrence Techniques at UK Landfill Sites.” International Journal of Pest Management, vol. 53, no. 4, 2007, pp. 347–356., doi:10.1080/09670870701421444.

Burger, Joanna, and Michael Gochfeld. “Behavior of Nine Avian Species at a Florida Garbage Dump.” Colonial Waterbirds, vol. 6, 1983, pp. 54–63., doi:10.2307/1520967.

Cook, Aonghais & Rushton, Steven & Allan, John & Baxter, Andrew. “An Evaluation of Techniques to Control Problem Bird Species on Landfill Sites.” Environmental Management, 2008, 41. 834-43. 10.1007/s00267-008-9077-7.

Curtis, Paul D.; Smith, Charles R.; and Evans, William, "Techniques for Reducing Bird Use at Nanticoke Landfill Near E. A. Link Airport, Broome County, New York" (1993). 6 - Sixth Eastern Wildlife Damage Control Conference, 1993.

Federal Aviation Administration. Advisory Circular 150/5200 34A “Construction or Establishment of Landfills Near Public Airports.” 2006.

Potier, Simon, et al. “Sight or Smell: Which Senses Do Scavenging Raptors Use to Find Food?” Animal Cognition, vol. 22, no. 1, 26 Oct. 2018, pp. 49–59., doi:10.1007/s10071-018-1220-0.

Slate, Dennis, et al. “Controlling Gulls at Landfills.” Proceedings of the Vertebrate Pest Conference, vol. 19, 2000, doi:10.5070/v419110223.

Loomacres Wildlife Management

E. Darby Albrecht

Kai Schafer

Brooke Morgan

800-243-1462

[email protected]