Road-based survey for estimating Wild Turkey densities in New Kingston, NY

Abstract: I conducted an eastern wild turkey survey (Meleagris gallopavo silvestris) in the New Kingston Valley in New York. I was comparing winter to spring changes in activity as the spring turkey breeding patterns began. A total of 261 turkeys consisting of 97 males and then 164 females. Weather extremely effected the study, as winter weather pushed into early April causing some breeding to be later. I observed the highest amount of turkeys on the 1st survey day while turkeys were in their winter groups, by April the gobblers and hens broke into small groups and began to move further into the valley.

The wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) is one of the most popular game birds across the country (NWTF). There are 5 different subspecies of wild turkey in the United States including Eastern wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo silvestris), Osceola wild turkey (M. g. osceola), Rio Grande wild turkey (M. g. intermedia), Merriam's wild turkey (M. g. merriami) and the Gould’s wild turkey (M. g. Mexicana). The eastern wild turkey has the highest population of the 5 different subspecies in the United States. Wild turkeys are an example of a successful conservation effort because in the 19th century into the early 20th century, turkeys were on the decline but with the use of capture and relocation, turkey populations rebounded (Bond et al. 2012).

Road-based surveys for estimating population densities of wildlife have been used for many different species such as mountain quail (Oreortyx pictus), red-legged partridge (Alectoris rufa), ring-necked pheasants (Phasianus colchicus), wild turkeys, and red-tailed hawks (Buteo jamaicensis) (Erxleben et al. 2010). Road-based surveys for wild turkeys can help in getting a better insight into the densities of populations in areas. Road-surveys that are paired with a spring and fall harvest indexes is best (Lint et. Al. 1995).

The New Kingston Valley is dense with different types of wild turkey habitat components such as agriculture, maple and oak forests, and river bottoms (Miller et al. 1999). The purpose of this study is to a road-based survey to measure the species densities of the Eastern Wild Turkey that is resident of the New Kingston Valley. I believe that I will find that in February-March, I will see turkeys remaining in large groups but males will begin to gobble strut in late march, and in April the large groups of turkeys will begin to break up and separate as the breeding season begins. The importance of using as much data for this survey is extremely important and paired with vocalizations of males and females heard (Lint et al. 1995).

Study Area

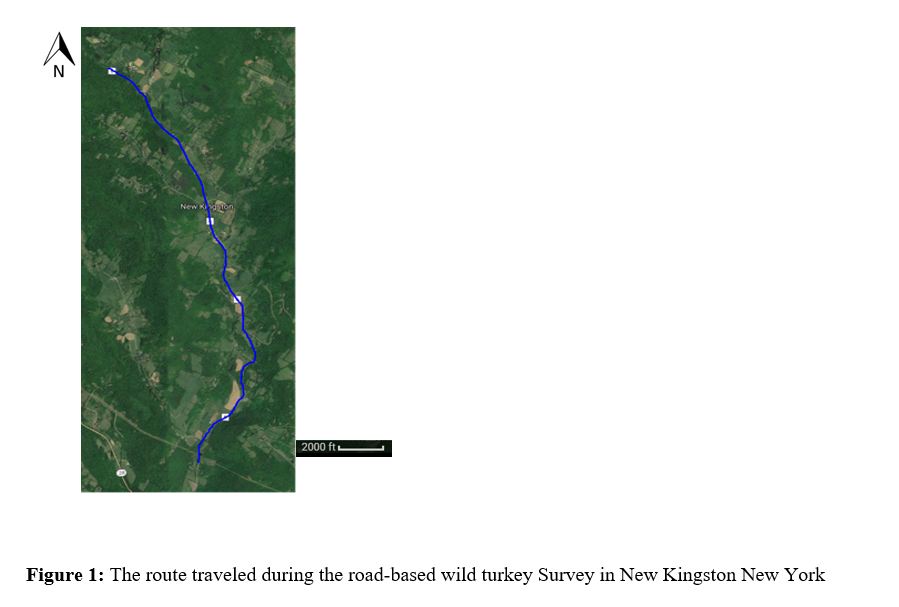

I conducted this study in the New Kingston Valley in New Kingston, New York. I drove along Delaware County Route 6 for 12 km 8 times from February through April 2018 (Figure 1). The elevation is about 274.3 meters above sea level. The route had a diverse amount of different vegetation types including agriculture fields with corn, hay, and mixed forests with maple (Acer), oak (Quercus), and beech (Fagus) but the valley was dominated by agriculture which makes it suitable for wild turkeys. Large portions of agriculture are separated by large parcels of wooded areas providing plenty of cover for almost any type of wildlife. There is also a small river that flows through the valley following the road that is traveled.

Abstract: I conducted an eastern wild turkey survey (Meleagris gallopavo silvestris) in the New Kingston Valley in New York. I was comparing winter to spring changes in activity as the spring turkey breeding patterns began. A total of 261 turkeys consisting of 97 males and then 164 females. Weather extremely effected the study, as winter weather pushed into early April causing some breeding to be later. I observed the highest amount of turkeys on the 1st survey day while turkeys were in their winter groups, by April the gobblers and hens broke into small groups and began to move further into the valley.

The wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) is one of the most popular game birds across the country (NWTF). There are 5 different subspecies of wild turkey in the United States including Eastern wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo silvestris), Osceola wild turkey (M. g. osceola), Rio Grande wild turkey (M. g. intermedia), Merriam's wild turkey (M. g. merriami) and the Gould’s wild turkey (M. g. Mexicana). The eastern wild turkey has the highest population of the 5 different subspecies in the United States. Wild turkeys are an example of a successful conservation effort because in the 19th century into the early 20th century, turkeys were on the decline but with the use of capture and relocation, turkey populations rebounded (Bond et al. 2012).

Road-based surveys for estimating population densities of wildlife have been used for many different species such as mountain quail (Oreortyx pictus), red-legged partridge (Alectoris rufa), ring-necked pheasants (Phasianus colchicus), wild turkeys, and red-tailed hawks (Buteo jamaicensis) (Erxleben et al. 2010). Road-based surveys for wild turkeys can help in getting a better insight into the densities of populations in areas. Road-surveys that are paired with a spring and fall harvest indexes is best (Lint et. Al. 1995).

The New Kingston Valley is dense with different types of wild turkey habitat components such as agriculture, maple and oak forests, and river bottoms (Miller et al. 1999). The purpose of this study is to a road-based survey to measure the species densities of the Eastern Wild Turkey that is resident of the New Kingston Valley. I believe that I will find that in February-March, I will see turkeys remaining in large groups but males will begin to gobble strut in late march, and in April the large groups of turkeys will begin to break up and separate as the breeding season begins. The importance of using as much data for this survey is extremely important and paired with vocalizations of males and females heard (Lint et al. 1995).

Study Area

I conducted this study in the New Kingston Valley in New Kingston, New York. I drove along Delaware County Route 6 for 12 km 8 times from February through April 2018 (Figure 1). The elevation is about 274.3 meters above sea level. The route had a diverse amount of different vegetation types including agriculture fields with corn, hay, and mixed forests with maple (Acer), oak (Quercus), and beech (Fagus) but the valley was dominated by agriculture which makes it suitable for wild turkeys. Large portions of agriculture are separated by large parcels of wooded areas providing plenty of cover for almost any type of wildlife. There is also a small river that flows through the valley following the road that is traveled.

Methods

From 10 February to 14 April 2018, I conducted a road based survey of wild turkey examining behavioral differences from winter to spring as breeding season approached. I used my vehicle to travel a 12 km route several times on each surveying day. The survey was conducted during a 63-day period, and turkeys were surveyed 8 of those days. While driving the route I would maintain a speed of 30-35 km per hour (Butler et al. 2007) unless safety precautions dictated a slower speed.

Sunrise varied each survey day, I always checked the daily sunrise the night before and planned to start surveys 30 minutes before sunrise. I randomly stopped and listened at good vantage points for gobbles or yelps of roosted turkeys during pre-dawn (Hoffman 1991). These vantage points consisted of hill tops looking and listening into the valley. In the valley vantage points consisted of field edges. When turkeys were observed, I would pull off to the side of the road and shut the vehicle off to avoid disturbances. Then, I would take 10-15 minutes to observing specific behaviors such as feeding, aggression, breeding, strutting, etc. through the Nikon Monarch 10x42 binoculars. I also used a Canon Rebel t6 with a 55mm lens and 75-300mm zoom to take pictures of turkeys. During the 10-15 minutes of observation, I would keep documentation of total individuals, number of males/females, gobbles, yelps, strutting activity, and other behaviors. Data from all survey days was then compiled together comparing total male and female, activity types, and vocalizations.

From 10 February to 14 April 2018, I conducted a road based survey of wild turkey examining behavioral differences from winter to spring as breeding season approached. I used my vehicle to travel a 12 km route several times on each surveying day. The survey was conducted during a 63-day period, and turkeys were surveyed 8 of those days. While driving the route I would maintain a speed of 30-35 km per hour (Butler et al. 2007) unless safety precautions dictated a slower speed.

Sunrise varied each survey day, I always checked the daily sunrise the night before and planned to start surveys 30 minutes before sunrise. I randomly stopped and listened at good vantage points for gobbles or yelps of roosted turkeys during pre-dawn (Hoffman 1991). These vantage points consisted of hill tops looking and listening into the valley. In the valley vantage points consisted of field edges. When turkeys were observed, I would pull off to the side of the road and shut the vehicle off to avoid disturbances. Then, I would take 10-15 minutes to observing specific behaviors such as feeding, aggression, breeding, strutting, etc. through the Nikon Monarch 10x42 binoculars. I also used a Canon Rebel t6 with a 55mm lens and 75-300mm zoom to take pictures of turkeys. During the 10-15 minutes of observation, I would keep documentation of total individuals, number of males/females, gobbles, yelps, strutting activity, and other behaviors. Data from all survey days was then compiled together comparing total male and female, activity types, and vocalizations.

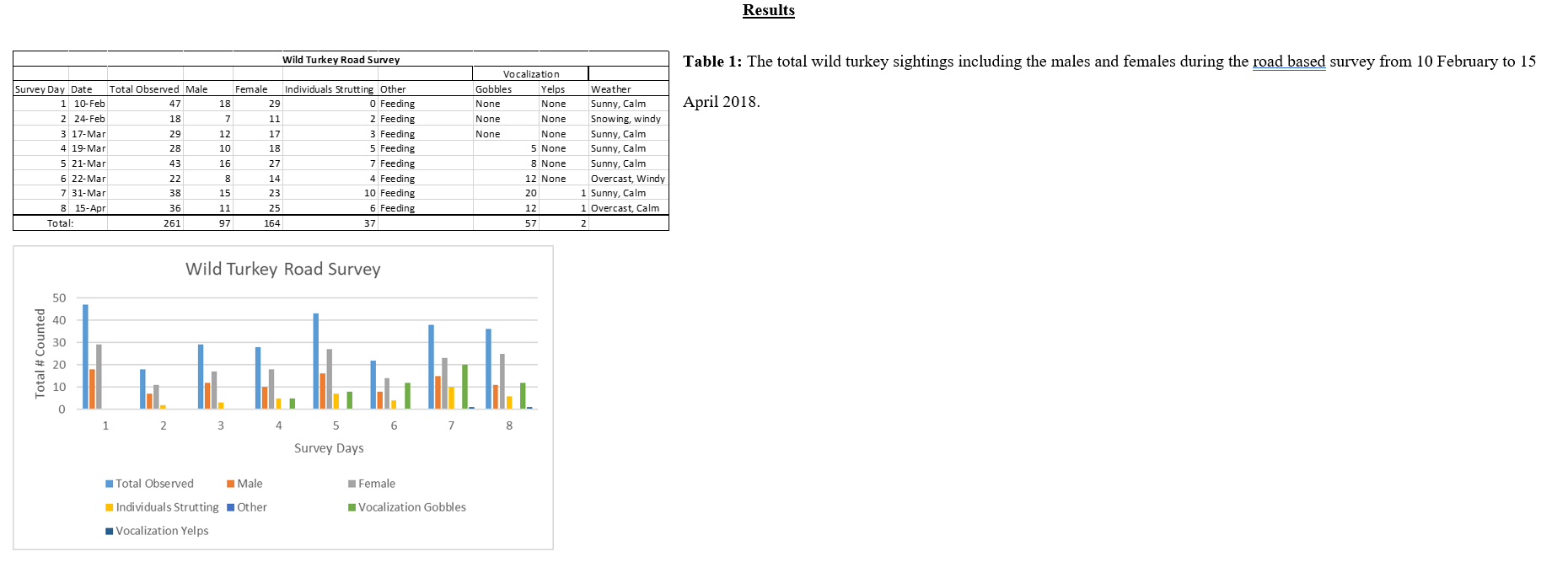

Figure 2: The trend of how many wild turkeys were observed and how their behaviors began to change as the further into time the study went.

The road-based survey of Wild Turkeys in New Kingston, NY was conducted over 8 survey days that ranged from February to April. A total of 261 individual turkeys were observed during the study, which had a total of 97 males and 164 females making a 2:1 female to male ratio. There was a total of 37 individual males observed strutting and another 57 gobbles, while only 2 yelps heard from the road (Table 1). In Figure 2, the bar graph shows the trend of the turkeys observed over the 8 observation days.

Discussion

I observed wild turkeys along an established route and documented the turkeys I observed during the 8 surveying days. As I surveyed turkeys across the 8 outings I was able to see out a trend developed and watch how they interacted with each other. The 1st survey day was my highest recorded total of 47 turkeys observed. I saw all 47 in 2 spots on far sides of my route. They were in the field together in their weather pattern grouped together at an active farm where manure was being spread and acting as an important food source. Areas where there are different kinds of agriculture that leaves corn or soybean stubble on the ground it provides a great food source and is extremely desired over other food sources such as hardwood crops or an abandoned field (Vander Haegen et. al 1989). In Kilpatrick et al (1988), he found that it turkeys during the winter also prefer conifer roost trees with dense limbs to protect them from the cold winter elements. This is another reason why turkeys from the whole New Kingston Valley may have found their way to these spots as there was low lying conifers such as Pine (Pinus) and Hemlock (Tsuga).

Weather was an extremely limiting factor of my study as the winter weather carried into the middle of April. It had an impact on if the hens were ready to breed. Hens being ready to breed is determined by photoperiod but passed springs that were warm early breeding has begun early. But based on this project the breeding season may be late this year. Survey day 8 the male gobblers started to show signs that they were ready as the morning was a typical warm morning. Gobblers were out strutting and the groups had broken up and I was seeing birds in areas I hadn’t seen them earlier in the study. Also being extremely vocal on 15 April 2018, as they gobbled a couple dozen times. Based on my results, I think that the New Kingston has a sustainable amount of turkeys for the future. The breeding season may be later this year than the year prior but based on my last survey day gobblers and hens were in small groups and beginning to start the breeding phase.

Literature Cited

Bond, B.T., G. D. Balkcom, C. D. Baumann, and D. K. Lowrey. 2012. Thirty-year case study showing a negative relationship between population and reproduction indices of eastern wild turkeys in Georgia. Georgia Journal of Science 70:164-171.

Butler, M. J., W. B. Ballard, M. C. Wallace, and S. J. Demaso,. 2007. Road-based surveys for estimating Wild Turkey density in the Texas rolling plains. The Journal of Wildlife Management 71:1646-1653

Erxleben, R. D., M. J. Butler, W. B. Ballard, M. C. Wallace, J. B. Hardin, and S. J. Demaso. 2010. Encounter rates from road-based surveys of rio grande wild turkeys in Texas. The Journal of Wildlife Management 74:1134-1140

Hoffman, R. W. 1991. Spring movements, roosting activities, and home-range characteristics of male merriam's wild turkey. The Southwestern Naturalist 36:332-37.

Kilpatrick, H. J., T. P. Husband, and C. A. Pringle. 1988. Winter roost site characteristics of eastern wild turkeys. The Journal of Wildlife Management 52: 461-63.

Lint, J. R., B. D. Leopold, and G. A. Hurst. 1995. Comparison of abundance indexes and population estimates for wild turkey gobblers. Wildlife Society Bulletin 23:164-168

Miller, D. A., G. A. Hurst, and B. D. 1999. Leopold. Habitat use of eastern wild turkeys in central Mississippi." The Journal of Wildlife Management 63:210-22.

Vander Haegen, M., M. W. Sayre, and W. E. Dodge. 1989. Winter use of agricultural habitats by wild turkeys in Massachusetts. The Journal of Wildlife Management 53: 30-33.

Wild Turkey Habitat. NWTF. <https://www.nwtf.org/hunt/wild-turkey-basics/habitat>. Accessed 29 Mar 2018.

Eric Mathiesen Loomacres Airport Wildlife Biologist

SUNY Cobleskill Department of Fisheries, Wildlife and Environmental Studies

State University of New York,

Cobleskill, N.Y. 12043 USA

April 21, 2018

The road-based survey of Wild Turkeys in New Kingston, NY was conducted over 8 survey days that ranged from February to April. A total of 261 individual turkeys were observed during the study, which had a total of 97 males and 164 females making a 2:1 female to male ratio. There was a total of 37 individual males observed strutting and another 57 gobbles, while only 2 yelps heard from the road (Table 1). In Figure 2, the bar graph shows the trend of the turkeys observed over the 8 observation days.

Discussion

I observed wild turkeys along an established route and documented the turkeys I observed during the 8 surveying days. As I surveyed turkeys across the 8 outings I was able to see out a trend developed and watch how they interacted with each other. The 1st survey day was my highest recorded total of 47 turkeys observed. I saw all 47 in 2 spots on far sides of my route. They were in the field together in their weather pattern grouped together at an active farm where manure was being spread and acting as an important food source. Areas where there are different kinds of agriculture that leaves corn or soybean stubble on the ground it provides a great food source and is extremely desired over other food sources such as hardwood crops or an abandoned field (Vander Haegen et. al 1989). In Kilpatrick et al (1988), he found that it turkeys during the winter also prefer conifer roost trees with dense limbs to protect them from the cold winter elements. This is another reason why turkeys from the whole New Kingston Valley may have found their way to these spots as there was low lying conifers such as Pine (Pinus) and Hemlock (Tsuga).

Weather was an extremely limiting factor of my study as the winter weather carried into the middle of April. It had an impact on if the hens were ready to breed. Hens being ready to breed is determined by photoperiod but passed springs that were warm early breeding has begun early. But based on this project the breeding season may be late this year. Survey day 8 the male gobblers started to show signs that they were ready as the morning was a typical warm morning. Gobblers were out strutting and the groups had broken up and I was seeing birds in areas I hadn’t seen them earlier in the study. Also being extremely vocal on 15 April 2018, as they gobbled a couple dozen times. Based on my results, I think that the New Kingston has a sustainable amount of turkeys for the future. The breeding season may be later this year than the year prior but based on my last survey day gobblers and hens were in small groups and beginning to start the breeding phase.

Literature Cited

Bond, B.T., G. D. Balkcom, C. D. Baumann, and D. K. Lowrey. 2012. Thirty-year case study showing a negative relationship between population and reproduction indices of eastern wild turkeys in Georgia. Georgia Journal of Science 70:164-171.

Butler, M. J., W. B. Ballard, M. C. Wallace, and S. J. Demaso,. 2007. Road-based surveys for estimating Wild Turkey density in the Texas rolling plains. The Journal of Wildlife Management 71:1646-1653

Erxleben, R. D., M. J. Butler, W. B. Ballard, M. C. Wallace, J. B. Hardin, and S. J. Demaso. 2010. Encounter rates from road-based surveys of rio grande wild turkeys in Texas. The Journal of Wildlife Management 74:1134-1140

Hoffman, R. W. 1991. Spring movements, roosting activities, and home-range characteristics of male merriam's wild turkey. The Southwestern Naturalist 36:332-37.

Kilpatrick, H. J., T. P. Husband, and C. A. Pringle. 1988. Winter roost site characteristics of eastern wild turkeys. The Journal of Wildlife Management 52: 461-63.

Lint, J. R., B. D. Leopold, and G. A. Hurst. 1995. Comparison of abundance indexes and population estimates for wild turkey gobblers. Wildlife Society Bulletin 23:164-168

Miller, D. A., G. A. Hurst, and B. D. 1999. Leopold. Habitat use of eastern wild turkeys in central Mississippi." The Journal of Wildlife Management 63:210-22.

Vander Haegen, M., M. W. Sayre, and W. E. Dodge. 1989. Winter use of agricultural habitats by wild turkeys in Massachusetts. The Journal of Wildlife Management 53: 30-33.

Wild Turkey Habitat. NWTF. <https://www.nwtf.org/hunt/wild-turkey-basics/habitat>. Accessed 29 Mar 2018.

Eric Mathiesen Loomacres Airport Wildlife Biologist

SUNY Cobleskill Department of Fisheries, Wildlife and Environmental Studies

State University of New York,

Cobleskill, N.Y. 12043 USA

April 21, 2018