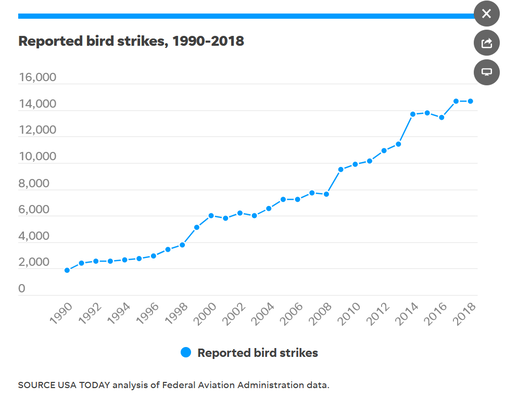

Over the past 30 years, the FAA has estimated that at least one plane a day is forced to land prematurely due to a collision with wildlife costing airlines $700 million in damages annually. The reality of the problem is that airplanes collide with birds and other wildlife at an astonishing rate because almost everywhere you look wildlife is living on or around airports. The Federal Aviation Administration has reported that nearly 9,000 birds are struck every year and those are just the ones being reported, So the number is estimated to be almost north of 20,000 every year. In 2018 USA Today did a story where they revealed that planes hit at least 40 birds a day! The FAA has identified 482 bird species that were hit in the U.S. from 1990 through 2019. Airplanes run into loons, starlings, grebes, pelicans, cormorants, herons, storks, egrets, swans, ducks, vultures, hawks, eagles, cranes, sandpipers, gulls, pigeons, cuckoos, owls, turkeys, blackbirds, crows, chickadees, woodpeckers, hummingbirds, mockingbirds, parrots, bats—as well as various kinds of geese. (Animals, such as deer, struck on the ground during takeoffs and landings also make up a meaningful portion of kills.) So why are Geese singled out so much? Well simple, their large body size, large flock size and sheer ability to cause damage on impact make them a huge target when applying wildlife management resources on your airport. The USDA says that of 10,000 plus avian strikes reported every year Geese make up about 1% of them. Of those Geese killed about 80% of them were resident geese not migratory. The biggest problem, however, has to do with the land surrounding airports. As a buffer to urban centers, most airports include a lot of undeveloped land around them. Hearty birds find this and use it as a refuge, depending on what plant, water and other natural resources are available. Solution Time! Ok so we know geese are a huge problem how do we fight back? Non-Lethal Management Practices tends to be employed first by just about everyone in the industry. These consist of using any means necessary to detour or disperse the geese from staging on or near the airport. Here are a few techniques used to harass the geese and scare them away.

Lethal Management Practices are typically used in extreme cases of either over population or too much potential risk! Although depredation is usually the last resort it absolutely is the most effective. Goose mitigation whether it be destroying and oiling goose nests in the spring or shooting a few as needed almost always clears the resident geese from coming back. The FAA has really done a great job encouraging airport operators to secure grants for funding programs such as a Wildlife Hazard Assessment and Wildlife Hazard Management Plan. These programs allow private companies like Loomacres Wildlife Management Inc. to come to your airport and conduct a wide range of tests, surveys, and research to help identify how great a risk Geese and other species are on your airport. From there Loomacres will provide you with a WHMP basically an action plan with how to address these issues and how to allocate resources to do so. Loomacres also provides FAA Approved Training Seminars for your airport staff and airport operators. But most of all it is a one stop shop for all your airport wildlife management needs. As the first privately owned FAA approved airport wildlife management company, our staff of Airport Certified Biologists are trained and experienced enough to irradicate any issue. So, stop losing the battle in the skies and fill out the fields below to speak with someone at Loomacres for a free consultation.

0 Comments

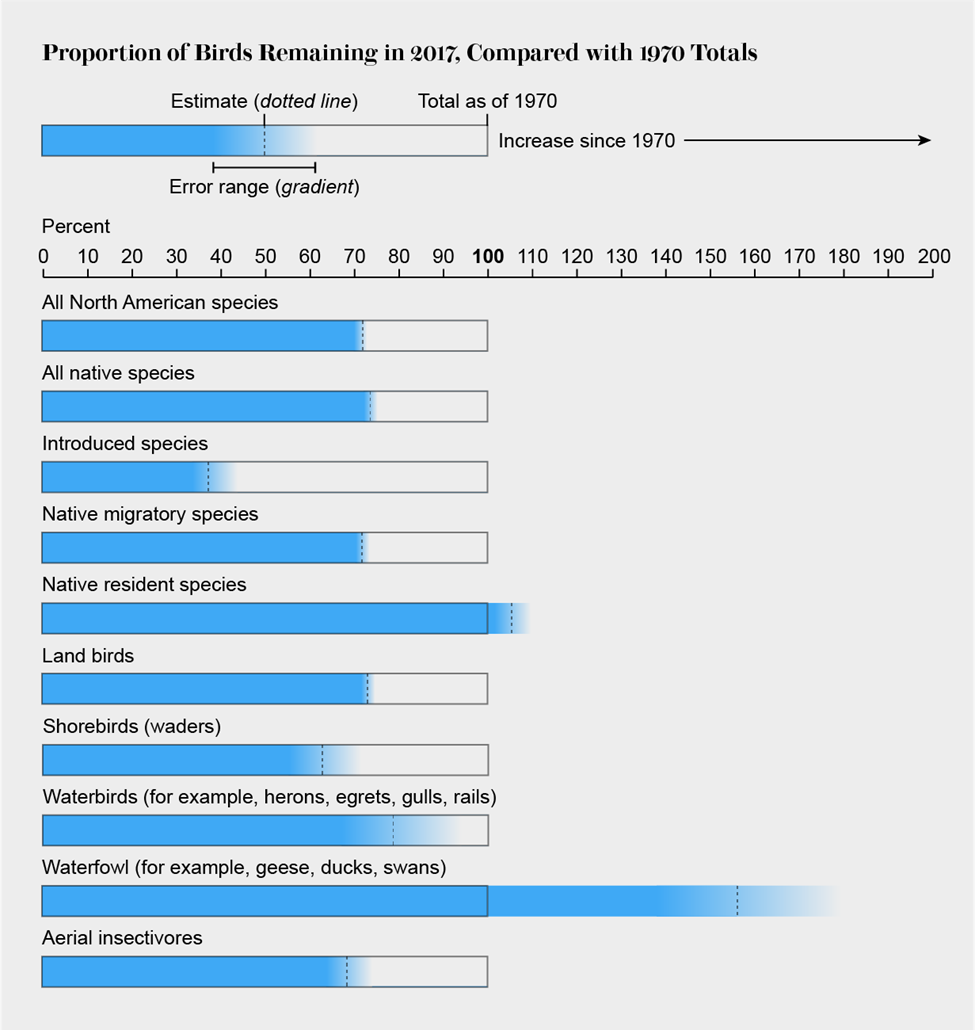

Watching waterfowl migrate south in the winter and north in the spring is one of mother nature’s timely gifts we get to enjoy every year. However, for an airport operator this tends to be their worst nightmare for air safety! Bird strikes happen every day on airports, but the risks are never higher at the peak of waterfowl migration. Companies like Loomacres Wildlife Management and their staff of Wildlife Biologist must ramp up efforts to detour waterfowl from roosting and nesting on stormwater retention ponds or feeding on airfields and nearby crops. During the migration season airports, and airliners loose millions of dollars a year due to collisions with ducks and geese simply passing through, or looking for food, water, and a place to sleep. At Loomacres we have clients in all 4 migratory flyways in North America (Atlantic, Mississippi, Central, and Pacific) and this year the reports from our Airport Wildlife Biologists have all been consistent with the trend that there just isn’t a lot Ducks and Geese Migrating. But there is a silver lining that is kind of alarming and sad at the same time. According Ducks Unlimited, in 2019 the breeding duck population was estimated at 38.9 million breeding ducks in the which is 6 percent lower than last year’s estimate of 41.2 million and 10 percent above the long-term average (see more). These numbers have continued to fall in 2019, and 2020 according to Wildfowl Magazine, and don’t ask any hunters about the decreased daily bag limits that have seen up to a 50% reduction in states like New York and Maryland. Is it just waterfowl that is disappearing? Nope, Scientific America has seen a decrease in total bird population drop 29% since 1970 which equates to a 3 Billion drop in population! See Chart Below. From the graph above you can see that Waterfowl made a huge surge due to conservation efforts till 2017 but have dropped by an average of 5.8% the last three years. So, where the heck have, they gone and what does this mean for Airport Operators? Simply it is a double edge sword scenario. On the one hand less birds less airstrikes but no birds equal more human destruction. It does not take a Wildlife Biologist to see that our human impact on land development and increased population (do not get me started on Global Warming) has significantly reduced the habitat for all living creatures on this planet but specifically in the United States. Will we see a healthy population of migrating ducks and geese level out? We shall see, but for now Airports and Airport Operators are enjoying clear skies but for how long and at what cost.

Management strategies for coyotes should start with understanding the true threat they can be when it comes to air safety. The habitat that airports provide for small birds, and mammals is a huge attractant for coyotes. These animals are extremely adaptive to their ever-changing habitat. Coyotes are members of the Canidae family and share a lot of the same traits of their relatives: wolves, dogs, foxes, and jackals. They have narrow, elongated snouts, lean bodies, yellow eyes, bushy tails, and thick fur. Coyotes are about as big as medium-size dogs, though they are smaller than wolves. They are 32 to 37 inches (81 to 94 centimeters) from head to rump, according to National Geographic. Their tail adds another 16 inches (41 cm) to their length. Coyotes typically weigh about 20 to 50 lbs. (9 to 23 kilograms) This species can thrive in forests, farmlands, prairies, mountains, deserts, and swamplands. Coyote populations are known to exist in 46 states, and it is possible that coyotes will soon be present in all states except Hawaii. Coyotes can adapt to populated areas, and thousands of coyotes living within the city limits of Los Angeles (see story) have led to severe management problems. And its not just Los Angeles its everywhere! In the airport wildlife management industry, we at Loomacres have had to delegate more and more resources to coyote control. They are extremely resilient and should not be taken lightly when trying to trap or depredate. So here are some tips for trapping coyotes on airports

These are just a few techniques we have adapted and found successful when trapping coyotes on airports. If you have more techniques you would like to share or for more information, please fill out the fields below.  Managing wildlife on airports is a never-ending battle. This battle is fought two different ways, lethal and non-lethal. Most wildlife is attracted to airport environments because it typically holds what they crave, food, water, and shelter. As the population of humans increase and so does the love for land development, airports become more and more of a hotspot for birds and mammals to take refuge. One rule of thought is that the most effective way of managing wildlife on airports is to modify or remove the attractants so that wildlife avoids the airport all together. Non-lethal management practices are often referred to as hazing or habitat management. Unfortunately, this method can never be 100% successful because of the highly adaptable nature of most wildlife species. This makes it extremely difficult and a time intense task. This creates a huge problem for all airport operators since courts have determined that airport operators are responsible for keeping a safe, wildlife free facility, and is obligated to warn flight crews of any activity. Private companies like Loomacres Wildlife Management Inc. become extremely important and can be an airports best friend for supplying tactics and executing proper techniques to mitigate wildlife risks. The first step in implementing a wildlife management plan on airfields is to perform a risk assessment. If you do not have data already on file you can begin by observing the wildlife that is using the airport. Set up in different places at different times of the day and night and simply observe and report. This will paint a clear picture of what species may be living on the airfield or somehow getting into the airfield. Second continue collecting and analyzing wildlife strike data to identify the species struck by aircrafts. The last thing and most important is to run a report in the FAA Strike Database. Some will run this dating back to the last 10 years or more. This may sound like an extremely time-consuming process and for the most part it is. However, the data will be used to allocate resources once your WHMP is put into place. Airports that are typically at high risk and in much need of implanting a plan immediately usually have a history of high strike rates or tend to be located near lakes, rivers, or other large bodies of water attracting migratory waterfowl. Also, airports that have landfills near by will also be at higher risk of strikes at an alarming rate. These airports must implement a rather aggressive wildlife control program. Once a risk assessment is concluded the data is used to customize a WHMP (Wildlife Hazard Management Plan). A well-developed plan will outline not only strategies but also allocations of wildlife control resources and includes information on the following:

Although not all encompassing, the bullets summarize issues that are typically addressed in an airport wildlife management plan. The short term and long-term success of an airport wildlife control program is very much dependent on a formal risk assessment and management plan, and the cost associated with developing the risk assessment and management plan will be recovered as success is realized. Perhaps even more important is the value provided by a formal, documented plan should legal action be taken by an air carrier following a damaging wildlife strike incident. It is also useful and cost effective to include in the planning process a professional biologist who has experience in wildlife hazard management which Loomacres can provide. Issues associated with natural science applications can be much more complex than first assumed, and current knowledge of effective wildlife management strategies and tactics is crucial to a successful plan. Finally, an airport wildlife management plan must be signed-off by the management team, demonstrating support and commitment for the program. Now that we have discussed some of the issues that provide a framework for the implementation of actions to manage wildlife hazards at an airport, we can conclude with a short discussion on passive and active management programs.

For more information or to contact Loomacres for a discussion of your current airport and needs, please fill out the fields below.  Bird predation of fish has become a major problem for fish farmers and is getting worse as problem bird populations increase. Most fish farmers already have experienced bird predation problems or will in the future that needs to be addressed for the sake of losing taxpayer money. Most fish-eating birds are opportunistic feeders and take whatever food is most easily accessible, so most fish hatcheries serve as a buffet. There are several birds that prey on fish. These include the double-crested cormorant, great blue heron, green-backed heron, little blue heron, black-crowned night heron, great egret, snowy egret, American white pelican, belted kingfisher, osprey, bald eagle, gulls, terns, and merganser ducks. These birds, except the merganser ducks, are protected by federal law and cannot be killed without a special federal permit. The merganser ducks can only be hunted during duck season under regulations applying to general duck hunting. Artificial rearing areas, heavily stocked during certain times of the year, attract these birds. Hatchery fish, having spent all their lives in protected environs, tend to be naive about predators. Although the fish are wary by nature, they may not, respond appropriately to a predator attack. When fish are stacked up in hatcheries, they are easier for birds to catch than are fish in a natural setting. Among the factors that affect the predator-prey relationship between fish eating birds and hatchery-reared fish are the size of the fish and the hatchery location. Hatcheries located near nesting sites, flyways, or estuaries routinely have severe avian predator problems. Coastal hatcheries in general have greater problems than inland hatcheries with fish lost to avian predators. Locations with naturally occurring populations of fish attract fish eating birds, and fish hatcheries are usually constructed near natural concentrations of fish. This results in an obscene amount of loss revenue for hatcheries that are unable to manage the wildlife and detour the birds from gorging on their profits. The most effective frightening device is increased human presence, which can also be the costliest. Some of the better scare devices are shellcrackers, whistle cartridges, bird bangers, screamer sirens, shotgun shells fired into the air, propane blast cannons, rope firecrackers, recorded bird distress calls, pop-up scarecrows that emit a loud noise as they are inflated, and balloon or other types of scarecrows that move in the wind. Any scarecrow or noise device must be moved around the facility for it to maintain effectiveness. Control measures must consider the type of predator they will be used against. Some measures are useful for a wide range of pests and others are useful only for specific types. Physical Devices can be designed for specific types of predators. If the predominant loss has occurred from wading birds such as herons, electric fences or low-level netting are effective deterrents. Some hatcheries have been successful in deterring herons by lowering the pond water level so that the birds cannot reach the fish. Some hatcheries have vertical walls with undermined walkways, these coupled with water level manipulations prohibit the birds from perching on the walls or wading into the ponds and reaching the fish. Where predators attack fish by diving from the air or from a perch, lines or wires placed over the tops of ponds are effective. These devices break up the flight pattern, although occasionally a bird is killed by the lines. Cormorants are difficult to keep away from large ponds. They have been known to swim under netting suspended at or below the water surface to get to fish. Some losses are so high that netting can be placed several feet below the surface of the water to give the fish protection. Physical control measures must be designed specifically for the hatchery as well as for the predator. With the population of wild fish such as salmon and trout decreasing with the demand of human consumption hatcheries are becoming more and more popular and needed to sustain healthy populations of fish. With this demand it seems to be apparent that the war between hatcheries and birds of prey is not going anywhere anytime soon. For more information, please fill out the fields below and someone from Loomacres Wildlife Management will contact you. |

Sales & Marketing

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed